In June 2023, I posted a blog to this site titled Top 200 Horror Movies of All Time/Horror Movie Watchlist in which I explained my intention to watch a list of my own creation, a list compiled through a process of my own devising from the six most popular top 100 horror lists I could find—lists from Rolling Stone, IGN, Rotten Tomatoes, Paste, Slant, and Bloody Disgusting—and added to that a selection of films too new to be considered by previous lists, international films from under-reviewed regions, and just some stuff that I had seen before and enjoyed. The process of compiling this list was complex, but I believed the watching and ranking of the films would be simple. You see these lists all the time. They must be easy to produce. The watching was a delight. But then came the ranking, and…well…

I’m gonna let you in on a little secret I discovered while crafting this list: ranking anything is an exercise in futility and lies.

When I began this project, armed only with my hubris and a desire to watch a bunch of horror films, many of which I’d seen, others I hadn’t, I imagined a time-consuming but clear-cut process; watch 200 films—no, sorry, make that 300, wait, ope, did you know new films come out ALL THE TIME?—and then narrow that down to the top 100 and rank them.

But as I watched film after film—316 at the final count—I began to see that in order to choose one film for the top 100 means you must also decide that another film doesn’t belong. For some movies that unworthiness is obvious. Like, in no universe does Mermaid: Lake of the Dead belong within a country mile of films like The Night of the Hunter, or Psycho, or Rosemary’s Baby, or even gnarlier, less refined fare such as A Nightmare on Elm Street or Return of the Living Dead. But for others, the difference in quality is less obvious. Also, the simple act of trying to hold one hundred of anything in your head simultaneously while plucking one from the whole and holding it up to compare it objectively to the 99 remaining is, well, let’s just say I don’t think the human brain was made for that. Now add to all of that the problem of whether the film in question is a great horror movie or a great film that happens to be horror. These might sound like the same thing, but there is a great gulf of difference between the two. Ask yourself this: is The Descent (2005) a better film than Don’t Look Now (1973)? Aside from the fact that two films couldn’t be less alike, this is a fairly straightforward question, and one that’s easy to answer. But now that you’ve had a chance to weigh those two films, consider this: which of them is a better horror movie? Which of them better achieves what most people expect a horror film to do? If your mind works as mine does, this is also a straightforward, easy-to-answer question, and one that has a completely opposite answer. Now extrapolate outward to take in one hundred films all needing an answer to these questions and you’ll begin to see how complex an endeavor like this one is.

After all of this, what you’re left with is a list of films that everyone is going to get mad about for one reason or another. And they should. A ranking, much like life, is unfair. Ultimately what I discovered is that in order to include every film worthy of inclusion, and every film that people expect me to have included on a list such as this, the list would need to be a bag of infinite holding, a TARDIS of Terror, bigger on the inside in order to accommodate every film that should well and truly have been included. Do I believe that Videodrome, or Black Sunday, or The House on Haunted Hill *actually* don’t belong on this list? No. They absolutely belong. And if I could fit more than a hundred films into a list of one hundred, they would for sure be there. But that’s an impossibility, one that anyone who’s ever tried to do this has surely had to contend with. So, I trimmed, and equivocated, and lied.

I lied.

Everyone who has ever made a ranking like this has lied to you. Little fibs to make it all fit. To tell a story, to craft a narrative of taste. To decide this film isn’t better, but it is more influential; This film isn’t scary, but it’s one of the best films ever made in any genre, and its genre just happens to be horror; This film was made on a shoestring and suffers from it, but it’s bolder, and funnier, and grosser than any other film before or since. It’s on the critic to decide that some lesser-known entry is better all around than it’s more famous sub-genre twin. And so, there it goes. Onto the list. And with its inclusion, there goes The Village of the Damned, off the list.

So here it is. The 100 “best” horror films of all time, half of which could be comprised of a completely different 50 films. If that makes you uncomfortable, if you need something more definitive, I’m sorry; I’m not the guy for that. Take comfort in knowing, though, that each one of these entries is as, if not more, worthy than any of the ones I left out. For now, because I am but one man, with other responsibilities, I will be releasing this list ten slots at a time beginning with 100-91.

100. Dead & Buried (1981)

Welcome to Potter’s Bluff: A New Way of Life!

After a photographer passing through the small town of Potter’s Bluff is brutally murdered by a group of townsfolk, who cover up their crime by staging it to look like a car accident, Sheriff Dan Gillis (James Farentino), assisted by the county coroner/mortician, the eccentric William G. Dobbs (Jack Albertson), opens an investigation. But it seems that each clue they discover only unearths more questions. When a local innkeeper claims to have seen the deceased photographer alive and well, working at the gas station down the road, the sheriff becomes embroiled in a case whose answers may lie on the other side of the veil.

At turns brooding and comedic—indeed the film went through copious re-toolings which did away with much, but not all, of the humor in Shusett’s script and left it somewhat tonally uneven—Dead & Buried is an undervalued gem in the horror canon. Written by Alien scribes Ronald Shusett and Dan O’Bannon (who, it should be noted, actually disavowed the film in a 1983 interview, stating that while he had worked on the screenplay, all of his contributions had been removed during retools) the film may have ultimately suffered from the studio engaging its entire marketing mechanism in attempting to tie Dead & Buried to the already iconic Alien. And to be sure, this film is nothing like the genre-breaking sci-fi horror masterpiece. Due to this studio chicanery, audience expectation may have hampered what should have otherwise been an immediate classic in its own right.

Dead & Buried has more in common with folk horror films like The Wicker Man or spooky mood pieces like John Carpenter’s The Fog than the science fiction terror of Alien—although I should probably warn you that with effects master Stan Winston on board, it is significantly more gruesome than either of those films. For this reason (though that makes it sound like it was the filmmakers’ fault instead of that of the fascistic bent of the UK at the time) Dead & Buried was designated a “video nasty” in the UK. Asked about influences on the film, Shusett cites the old EC Comics (much like Creepshow the very next year), an influence that becomes more and more apparent as the film’s shocking climax unfolds.

I have to admit to being somewhat surprised at how well this film holds up. Yes, it’s grainy, the editing isn’t exactly smooth, and no one would claim that its gender politics could pass a test of parity, but Stan Winston’s effects and a stellar ending that—even as a viewer raised on horror fiction and it’s tropes, both new and old, I found surprisingly bold—elevate it beyond much of its early 80s brethren. Dead & Buried truly was “a new way of life” for a growing undead genre still finding its identity.

99. Night of the Comet (1984)

After a once-in-65-million-years comet passes near Earth, immediately vaporizing into a red dust anyone unlucky enough to be caught outside during its passage and turning anyone partially exposed into violent ghouls, sisters Regina (Catherine Mary Stewart) and Samantha (Kelli Maroney) Belmont strike out across an eerily desolate Los Angeles in search of answers and other survivors.

Though writer-director Thom Eberhardt is largely unconcerned with frightening his viewers, his film sits undeniably within the horror genre, hitting a surprising number of contemporary zombie movie tropes—from main characters sleeping through the beginning of the apocalypse, to gangs of miscreants interested only in exercising their unchecked violence on others where the collapse of traditional power structures have left a void, to shadowy government organizations whose mysterious goals have nothing to do with the protection of our survivors. What Eberhardt is interested in, however, is character and sweet 80s vibes. Samantha, Regina, and Hector (Robert Beltran, Star Trek Voyager) are icons, and I would watch any number of adventures featuring this trio. To be honest, I’m a sucker for any entertainment property that treats Youth, in all of its vapid glory (Comet spends several minutes of its runtime on the best post-apocalyptic shopping spree ever put to film), as a strength instead of something to be ridiculed. One can’t help but see Regina and Samantha as the prototype for every Buffy that came after.

Few films are so perfectly, ridiculously of their time as Comet is, and yet so timelessly enjoyable.

98. Pontypool (2008)

Based on the novel Pontypool Changes Everything by Tony Burgess and directed by Bruce McDonald.

Grant Mazzy (Stephen McHattie) is a shock-jock from the big city who’s been knocked back to the minors after taking his schtick too far one too many times. From behind the mic of Mazzy in the Morning, his new morning radio show in the small town of Pontypool in rural Ontario, he and his producers bring the people of the little burg their news and weather while attempting to navigate the weirdest day of their professional lives. While host Grant, producer Sydney (Lisa Houle), and assistant Laurel-Ann (Georgina Reilly) are stuck in the studio, forced to trust the limited information they can gather from the show’s callers and Ken Loney, their Eye-in-the-Sky reporter, the loyal listeners of Pontypool are being infected with a virus that lives inside the spoken word, turning them vicious and violent, a zombie apocalypse that hangs on Grant Mazzy’s every word. If the idea of a horror film that stands as a metaphor for journalistic integrity and the real-world violence that can be spawned by the simple act of speaking doesn’t grab you, then we, dear reader, are fundamentally different people.

97. Return of the Living Dead (1985)

Braaaaaiiiins.

John Russo and Dan O’Bannon’s The Return of the Living Dead has a complicated pedigree, but we’re not here for a history lesson. Suffice it to say that due to some oddities of copyright, after Night of the Living Dead, cowriter John Russo retained the use of the “…of the Living Dead” moniker while Romero was left having to use “…of the Dead.” Which gives us the novelty of a classic film having not one but two sequels: Romero’s Dawn of the Dead (1978) and Dan O’Bannon and John Russo’s The Return of the Living Dead (1985), and for all the fluidity and shifting canon of Romero’s zombified world, the world of Return is even more confusing and meta. So, to set us up a little and let you know the sort of thing you’re in for, a little in-fiction history. I know I said we weren’t here for a history lesson, but lore is different, right? Right. Here we go: In the fictional world of Return of the Living Dead, in 1968, an unnamed director shot what would become a well-known independent film about an almost-apocalypse wherein the newly dead rose from their slumber and began to attack and devour their victims before the government eventually regained control and put an end to the ghoulish uprising. What fans of this film were never made privy to was that Night of the Living Dead was loosely based on a true story.

When the unknown young filmmaker first conceptualized his film, it was to be a factual retelling of the events surrounding an accidental release of the chemical 2-4-5 Trioxin (a play on Agent Orange or 2,4,5-T + 2,4-D) in the basement of a VA hospital, but before he could complete his film, the government confronted him and ordered in no uncertain terms his film to be shelved. So instead, he made what we, as well as the characters in Return, now know as Night of the Living Dead. The secret the government had been trying to keep the lid on was that this accidental release of 2-4-5 Trioxin had resulted in the reanimation of three corpses that then went on a rampage, killing several people before finally being subdued and captured by the military. When the military attempted to ship these reanimated corpses in sealed barrel tanks from the VA to a military base in California for study, they ended up lost.

Cut to 14 years later where Frank (James Karen) of Uneeda Medical Supplies is showing new hire Freddy (Thom Mathews) the ropes. In an attempt to impress the new kid, Frank tells him the true story of Night of the Living Dead. When Freddy asks how he came by this information, Frank tells the kid it’s because they have the three lost tanks complete with corpses right there in the building.

Return is a slapstick punk-rock horror-comedy more akin to the films of Sam Raimi than those of George Romero with a soundtrack to match. Songs from punk and psychobilly bands like The Cramps, 45 Grave, T.S.O.L., The Damned, and The Flesh Eaters imbue every scene with a goofy swagger, and together with some incredible costuming for the group of punk teens who get caught up in all this undead drama, lends the film an attitude that is so incredibly of its time that it all somehow comes back around to feeling timeless, iconic. The creature effects (by the Fantasy II Film Effects crew), especially for Tarman, God’s cutest little ghoul, are more assured, and more absurd, than many of Return’s contemporaries, and despite the comedic nature of the film, Dan O’Bannon (Alien) never forgets the intensity and carnage viewers expect from a zombie film.

Return of the Living Dead is a cult classic of the highest caliber.

96. Impetigore (2019)

Impetigore, or Perempuan Tanah Jahanam (literally, woman of the damned land) follows a tollbooth operator in Jakarta named Maya (Tara Basro), who after a bizarre encounter with a golok-wielding attacker who claims to be from Harjosari, the village where Maya was born, decides to travel back to this forgotten home. As a child, Maya’s parents shipped her off to live with her aunt in Jakarta under suspicious circumstances, and Maya is dying to know why. Enlisting the help of her friend Dini (Marissa Anita) and armed with new questions about who she is and where she came from, and about how her parents might be tied to her attacker, she returns to Harjosari for the first time since childhood. There, she hopes to find answers to these questions and possibly, hopefully, as the last of her line, to claim the inheritance of the village’s largest house. But in Harjosari, the two women find a village in turmoil, with babies dying every day from a strange illness, a curse, the villagers claim, and one they believe Maya’s family are responsible for.

And–bad news everybody! –the only way to end this curse is to sacrifice the one remaining member of Maya’s family—her, it’s her, it’s Maya, yeah, you get it.

Folk Horror is one of my chosen fields of study, so Joko Anwar’s stylish tale of a young woman returning to her ancestral village to claim an inheritance only to learn instead that sometimes a vast gulf exists between what is owed and what is received is totally my jam. All of the elements of the genre are here, from its classic structure—a protagonist seeking relief from modern society journeys back to the pagan wilds to reconnect with their roots only to find that those roots have rotted in their absence—to its themes of power derived from the excision and subsequent isolation of one’s cultural history, the growth of witchcraft for those left behind as a response to that power, and of the generational trauma and hereditary responsibility that arises in the face of this struggle, but in most of the folk horror film canon, in stark contrast to the rich global history and wide-ranging inspiration of folktales and dark folklore—and besides a very small handful of exceptions in the form of widely recognized folk horror films from Korea, Russia, and South and Central America—the genre has been largely represented by a glut of Eurocentric fare. And while it is these very same British, European, and American films (along with many a novel with this same focus) that drew me to the genre in the first place, it is refreshing to see a new voice emerge, drawing from the history of a culture as rich with folklore as Indonesia. Impetigore is such a beautifully shot, well-acted, and engrossing film, with such a strong embrace of its unique identity that I do not hesitate to add it to the ever-growing canon.

A short addendum: One of my favorite discoveries while working through this process has been the myriad horror films from Indonesia, specifically the works of Joko Anwar. It had been a blind spot for me, and I’m so glad to have remedied that. So, assuming you haven’t, check out Satan’s Slaves (2017) and The Queen of Black Magic (2019) if you’re looking for some deep, dark, but above all fun, stuff.

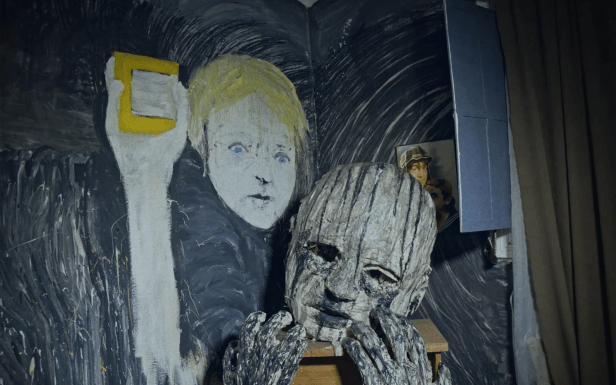

95. The Wolf House (2018)

The Wolf House is a stop-motion nightmare from Chilean creators Joaquín Cociña and Cristóbal León along with co-writer Alejandra Moffat. It follows a young woman named Maria who escapes from La Colonia, a barely-fictionalized version of Colonia Dignidad, the German isolated community in Chile, known for its honey and for its human rights atrocities in the mid-twentieth century. The film takes a clever tack in purporting itself to be a propaganda film produced by the commune.

Maria, who after escaping La Colonia and finding herself on the run from a Wolf who stalks her through the wilderness outside La Colonia, takes refuge in a dilapidated house. Inside, she finds two pigs which she befriends then eventually adopts as her own children as she gives them more and more human traits: First, hands. Then feet. Then clothes and names—Ana and Pedro. Then voices with which to speak.

And finally, hunger.

The three of them spend their days inside the house, afraid to leave because of the wolf who stalks just outside their door. But Maria makes a beautiful home for them.

The logic of the film is subjective, with rooms (and pigs) changing seemingly according to Maria’s whims. Maria isn’t so much an unreliable narrator as she is a local god. Characters, settings, and details are added (or painted over or removed completely) to the scene in real-time: Ana and Pedro, after being drenched in La Colonia honey, are repainted in shot with white skin and golden hair; a toilet is peeled away to reveal a wooden chair, a tray becomes an eye; a pile of fabric stitches itself into a still-life of fruits and tea cups; the tray that became an eye slides across the wall and becomes a landscape painting becomes a mirror becomes a two-dimensional person who then walks out of the wall and sucks up the surrounding elements of the room to become fully realized in three dimensions. It is messy, and unsettling, and gorgeous, and unending. The whole film is this shaking, quivering, lumbering body-horror cacophony of shape and form that one fears could at any moment come unraveled under the weight of Maria’s trauma.

It is an astounding achievement.

94. Deathdream (1974)

On the same night the Brooks family receives word that their son Andy has been killed in action in Vietnam, he returns home. The government must have made a mistake—surely that’s it—and why question it overmuch when everyone is so ecstatic about Andy’s miraculous return. Everyone, it seems, except for Andy himself. As the days pass, Andy retreats further and further into himself, refusing to see his girlfriend who’s been waiting on him to return from war, or any of his family’s friends who want desperately to visit with the young hero, and his father begins to worry about what this young man, so different from the charismatic son who left, might be hiding from everyone.

Touching on PTSD, the morality of war in general, and the reception soldiers receive upon their return home—a mix of worship and fear—Bob Clark’s (Black Christmas, A Christmas Story) and Alan Ormsby’s low-budget cult classic, also known under the alternate title Dead of Night, is a demented nightmare of the living dead that questions what it means to return home after being fundamentally changed by a war of choice.

93. The Invisible Man (2020)

Cecilia (Elizabeth Moss) has finally gathered the courage to leave her long-time boyfriend, wealthy optics engineer and serial abuser Adrian (Oliver Jackson-Cohen). Days after her middle-of-the-night flight, news of Adrian’s suicide reaches Cecilia where she’s staying with an old friend and his daughter, but the relief she feels at the news of Adrian’s demise is short-lived. Strange occurrences and coincidences start to stack up, and she begins to suspect that his suicide is nothing but a hoax, yet another ploy in a long line of manipulation tactics meant to garner sympathy and attention. Her friends and family, however, don’t share these suspicions, and Cecilia’s insistence that in the months before she left him, Adrian had been working on a suit capable of making the wearer invisible to the naked eye only reinforces their opinion that Cecilia is simply under too much stress. As everyone she knows begins to turn on her, and an unseen force targets her loved ones in increasingly violent ways, what will it take to make them believe her?

Leigh Whannell’s story of a woman on the run from her tech entrepreneur ex-boyfriend is a marvel of tension-building. Wide shots that draw the eye of the viewer to every corner of every room in this largely interior film for the fear that He might be lurking anywhere, unseen, are executed with a similar precision to It Follows, giving the sense that every inch of her surroundings are a threat; that after an experience like the one she endured under his controlling hand, one cannot trust anything or anyone. There have been many horror stories about the after-effects of abuse, but few have been as astute while still managing to operate as an effective horror-thriller.

Where mad-scientist horror classics like Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, The Fly (both versions), and the original James Whale-directed, Claude Rains-starring The Invisible Man focused mostly on the scientist’s hubristic fall, this updated take is all about the victim, and it’s a welcome change.

92. Who Can Kill a Child? (1976)

Narciso Ibanez Serrador’s Who Can Kill a Child? (Quien puede matar a un nino), based on the novel El juego de los ninos and released in the US as Island of the Damned, stars Lewis Fiander and Prunella Ransome as Tom and Evelyn, an English couple who have traveled to the coast of Spain to await a boat to carry them to the nearby island of Almanzora for a much needed getaway before the coming birth of their third child. Tom has visited Almanzora previously and believes his wife, Evelyn, will enjoy its quaint charms. Once on the island, however, the couple discover they’re the only adults around. And the children of the island are behaving…oddly.

Purposefully paced, dealing out its shocks in reluctant glimpses, Ibanez’s film requires the viewer to contemplate its titular question along with Tom and Evelyn—Who can kill a child, and at what point does such an act become excusable? From the 10-minute Mondo film opening (a type of exploitation documentary which explored taboo subjects) that presents the thesis that children around the world are disproportionally subject to the atrocities committed by adults and nations, and therefore are long overdue for their revenge, to the final gunfight, Who Can Kill a Child? is a grim affair. This is not a fun exploitation film—It wants you to consider, to roll its questions around in your mind until you’ve come up with a reason for our actions, and then it wants to shatter that reasoning. Like the children in the film, it wants to hurt you.

As we work through this list together, some of you will notice that I’ve included this film but not the original kids-vs-adults horror film, Village of the Damned, and while I did consider it—I even had Village on my list until the final pass—I ultimately decided that this one was more worthy of the spotlight. That said, if you haven’t seen the original 1960 Village of the Damned, you should definitely do that; it’s great. Another honorable mention in this subgenre is Eskil Vogt’s 2021 horror-thriller The Innocents.

Finally, a fun fact: Who Can Kill a Child? has some distinct similarities with Stephen King’s 1977 short story Children of the Corn and the subsequent films based on it. This is because, as Stephen King himself has said, Ibanez’s film was an influence on his story.

91. The Mist (2007)

In the aftermath of a devastating thunderstorm, a mysterious mist rolls into the town of Bridgton, Maine, bringing with it a menagerie of otherworldly monsters. Anyone unlucky enough to be caught in it does not last long. Trapped inside Food House grocery as the mist rolls in are a ragtag group that includes local artist David Drayton (Thomas Jane) and his son Billy, litigious neighbor Brent Norton (the great Andre Braugher), schoolteacher Amanda Dunfrey (The Walking Dead’s Laurie Holden), and the zealous Mrs. Carmody (a particularly terrifying Marcia Gay Harden) among other assorted store clerks, townsfolk, and soldiers. (Folks, we got ourselves a microcosm!) As the mist covers all, and the store’s inhabitants sort themselves into rival factions, the one thing that’s clear is that what’s happening outside the disconcertingly thin glass of the store’s window-lined façade is not the only danger.

Like Stephen King’s 1980 novella of the same name, Frank Darabont’s (The Shawshank Redemption, The Walking Dead) adaptation harkens back to the sci-fi horror films of the 1950s and 60s, such as The Blob, The Day of the Triffids, and the original Invasion of the Body Snatchers. In the same way those classics used their monstrous conceits to depict the fear and distrust brewing in our suburbs and small towns, Darabont’s film delves into the petty grievances and differing belief systems that can pull a community apart, putting the lie to the conventional wisdom that people come together in times of crisis. Its depiction of small town life, where heroes can be found working at the grocery store while villains preach the gospel, rings true in a way that continues to feel prescient. It is certainly a product of its time, having been released during the then extant wars and general upheaval of the George W. Bush years, but damned if we don’t keep behaving the same way.

Where much of the horror output of the 2000s was focused on a particularly dark brand of nihilism, The Mist offered a type of hope, grim though it was. Given its famous-in-its-own-right ending, it’s understandable if you think I’ve lost my mind calling this film hopeful, but its final message is explicit in its call to never give in to apathy. I consider it the greatest of the post-9/11 horror films.

90. Pearl (2022)

The second in Ti West’s X Trilogy sees the first film’s iconic villain as she once was. Pearl (Mia Goth) lives a life of drudgery with her immobile, stroke-survivor father (Matthew Sunderland) and dour, disapproving mother (Tandi Wright) on a secluded farm in WWI-era Texas. Reluctant to give into the austere life her mother wants for her, Pearl dreams in technicolor of a life in the limelight. Her big chance comes when she hears from her sister-in-law of a talent search for a dance troupe being held at the church. When she’s rejected, she spirals into a spree of madness and violence that precipitates the circumstances in which we find her during the events of X (2022).

Where X was a dusty, washed out descent into a 1970s Texas on the cusp of the pornography explosion, Pearl introduces us to a rural community bursting with vibrant innocence. Utilizing techniques that mimic the three-strip Technicolor process of films from the golden age of Hollywood, namely that of The Wizard of Oz, helps lend Mia Goth a Judy Garland innocence and wonder, and renders her violent descent as a journey of discovery.

Pearl is part The Wizard of Oz and part Psycho, a coming-of-rage story that, in the words of William Bibbiani of TheWrap, “retroactively makes its predecessor great…” It’s a film that, much like cult classic May (2002), asks what if we went so far to find love and acceptance that, in the process, we became undeserving of them.

89. His House (2020)

Remi Weekes’ feature debut tells the story of Bol (Sope Dirisu) and Rial (Wunmi Masaku), asylum seekers from Sudan who, upon their arrival in the UK, run up against the bureaucratic, Catch-22-esque nightmare of the immigration system and simultaneously must face the horrors they may have brought with them into their new home. Facing guilt and remorse over the loss of a child during their journey across the sea, the couple reacts in differing ways to the assimilation the asylum process requires. Threats of various natures, both supernatural and societal, within and without their government-subsidized home assail them at every turn, and the couple finds that there are no clear answers to any of their problems. They both grow to believe they’re being haunted, but their divergent beliefs about the nature and reason for said haunting creates a rift that threatens their new life before it’s even started.

The horrors of His House stems largely from this haunting, but the film also delves into questions of assimilation—how much of oneself is one willing to relinquish when even tragedies are an important, insuperable part of identity? What is lost through giving up that identity? What might be gained? Through the differing points of view of this husband and wife, the supernatural is turned on its head so often that eventually what we’re looking at starts to seem more psychological horror than anything so quaint as the hauntings or possessions of folk horror. The production design mirrors the fragile states of mind of these characters with the apartment’s peeling wallpaper and unfinished walls, and the sound design suggests rats in the brain as well as the walls.

Aside from periodic time jumps back to the couple’s flight from Sudan and subsequent sea crossing, the film is largely set inside the apartment and much care is taken to ensure the apartment itself tells the story of the couple’s descent. The acting from the two leads, as well as a seemingly sinister turn from Doctor Who’s Matt Smith, along with inventive set design, make for a film I’m confident will stick with you every bit as much as it has me.

88. Phantasm (1979)

Diminishing quality aside, Don Coscarelli’s Phantasm franchise has done a good job fleshing out its logic and themes over the years—each of the five films, according to some fans, representing the five stages of grief—but part of the original film’s charm is in not overexplaining the other hellish world that exists alongside ours or forcing us to choose one interpretation of its plot elements over another. The Tall Man (Angus Scrimm) either really exists and therefore so does the realm from which he comes, or the whole thing is the product of a mind in terrible grief and confusion. In this way, it is more akin to the work of classic folk horror authors like Arthur Machen, or equally obvious, the cosmic horror of H.P. Lovecraft. At the center of Coscarelli’s tale are two brothers, Mike (A. Michael Baldwin) and Jody (Bill Thornbury). The brothers have been recently orphaned, with 24-year-old Jody caring for 13-year-old Mike while attempting to balance his own desires with his new role as guardian. Meanwhile, Mike has started following his older brother around for fear that he will leave him behind in pursuit of his music career. When Mike’s stalking takes him to the funeral of one of his brother’s old bandmates, he witnesses strange occurrences, including the tall undertaker lifting a coffin and carrying it like it weighs nothing. Mike convinces Jody and their friend Reggie (Reggie Bannister) to investigate. What follows, and subsequently what went before, is up for interpretation, but I’m always a sucker for a story that mixes the cosmic with the personal, and Phantasm is one of the best to do it, due in no small part to the its depiction of the relationship between Mike, Jody, and Reggie. It’s a film about loss, but also about family finding you when you most need it. Also, there’s freaky little Jawa monsters and a desolate red planet on the other side of a portal in a funeral home. It’s the rare fever dream that follows a course of logic so tightly that it’s not till the end that you’re like, hey, wait a minute, what the hell just happened? It’s also visually stunning. In toto, it’s rad as hell.

87. The Masque of the Red Death (1964)

In the best film out of Roger Corman’s stellar series of Edgar Allan Poe adaptations, Vincent Price stars as Prospero, a European prince who rules over the peasants with a petty and tyrannical hand. When Prospero learns of a plague sweeping through the village, he orders it burned and shuts himself in his castle with the local nobility. But is the figure in red who stalks through the gathered merrymakers Prospero’s master, Satan, or is it something worse, something promising death for all, even for those who believe themselves untouchable through their wealth and servitude to the Dark Lord?

At turns garish and artful, macabre and playful, Corman’s film combines Poe’s Masque with another of his short works, “Hop-Frog,” a story about a man with dwarfism who becomes the king’s—in this case, Prospero’s—jester, using his new position to enact vengeance on his tormentors. Prospero faces off against these threats—angry villagers who seek to stop his satanic machinations and a man set on revenge—before finally coming face to face with the worst of all, a plague that doesn’t discriminate between wealthy and poor. Masque boasts one of the best Price performances, behind only The Abominable Dr. Phibes and Witchfinder General for sheer camp menace. This, along with Charles Beaumont’s screenplay that deftly combines these disparate elements into a thematically dense whole, lavish set pieces that rival some of the greatest films of the mid-twentieth century, and the best use of the color red outside of the giallo films of the following decade, makes Masque stand out as a particularly fine example of this film cycle.

86. What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962)

Decades after fading from the limelight, former child star “Baby” Jane Hudson cares for her paraplegic sister Blanche in the decaying mansion they share. Blanche, a retired actress whose talent and fame exceeded her older sister’s in every way, is reduced to an invalid under her sister’s version of care, and in turn Jane resents having her once-expansive life wasted on Blanche. The disdain the sisters hold for each other drips off the screen. Out of this resentment and jealousy, Jane torments Blanche, rendering her days in agony and depression. When young pianist Edwin Flagg comes calling with promises of new fame for Jane, it sets in motion a series of events that will upend the sisters’ sad existence, showing how far each is willing to go to escape their circumstances.

Mystery abounds in their hermitage, including questions of what exactly happened the night of Blanche’s accident years prior that left her confined to her. Will uncovering this heal the rift between the sisters, or will it all end in tragedy?

Perhaps I could just say “Bette Davis and Joan Crawford” and leave it at that, but Robert Aldrich’s film, based on the novel by Henry Farrell with a screenplay by Lukas Heller, is so much more than the behind-the-scenes feuding. Sure, Davis and Crawford play to chilling perfection a pair of sisters who despise—and depend on—each other, but with such an artfully made film about fame, rejection, mental illness, and the bonds that tie us together when nothing else is left, you’d be doing yourself a disservice in believing that’s the only reason we’re still talking about this film 60-plus years later. A paranoid thriller whose influence you can see throughout the intervening years in films as disparate as The Substance and Misery, Baby Jane? is a study in tension, paranoia, and the type of sibling rivalry that precludes neither hate nor love. The final scene on the beach is so effective to this day that even on my most recent viewing I found myself both distressed and laughing, a testament to the emotional depth and tonal deftness of a film that I’ve watched with pleasure so many times over the years.

85. I Walked With a Zombie (1943)

I Walked With a Zombie is a Val Lewton Production directed by Jacques Tourneur, so iykyk, but for those of you who don’t, that’s basically synonymous with quality in 1940s horror. In the span of two years the Lewton-Tourneur team produced three of the most beloved horror films in a decade overflowing with quality genre pictures. They hit the ground running with 1942’s Cat People—and rest assured we’re gonna talk about that one later—but Zombie is almost as good. This moody, atmospheric film follows a young Canadian nurse Betsy (Frances Dee) who is hired to take care of plantation owner Paul Holland’s (Tom Conway) sick wife Jessica (Christine Gordon) on the fictional island of St. Sebastian in the West Indies. Jessica has been behaving strangely and consensus among the other island dwellers points to her illness being the result of a brain fever, but signs begin to crop up that something more supernatural might be afoot. After a shock therapy treatment fails to cure Jessica, Betsy looks to the island’s Voodoo practitioners for help. There are those, however, who believe that Voodoo was initially to blame for Jessica’s almost catatonic state and so are reluctant, for varying reasons, to use it to heal her.

Let’s get this out of the way first and then we can move on: I Walked With a Zombie was made to appeal to a certain colonialist mindset that was still popular at the time by people who largely shared that worldview. However I was surprised at how progressive some of its thinking was in regards to how best to care for a people that differed culturally from the white protagonists, namely that they should be met on their own terms, not be preached to or converted or have their “backwards” beliefs bullied out of them. The film is racist, as racism is a system, but perhaps not bigoted as there doesn’t seem to be any hatred or disdain for these people or their ways. I found that oddly refreshing for a film like this. Obviously, your mileage may vary, and I’m just a white dude telling you, “It’s okay; just watch it,” when maybe that’s not my place to say, but I personally found it less offensive than I would’ve imagined, for whatever that’s worth.

Whatever your feelings, Zombie is a beautiful film with cinematography from J. Roy Hunt that remains crisp and clear despite so much of the film taking place in the dark. The depictions of the rituals are fascinating from a choreography and score standpoint, reminding me, for better or worse—mostly better—of certain scenes from King Kong (1933). Like most Lewton productions this is a story about how some things are worse than death, that death can be a release from this torturous existence. It’s this nihilist bent that sets these films apart from the Universal pictures that were popular during the same timeframe.

Finally, I’d like to take this opportunity, the first of many, owing to the nature of a project like this, to harp on a peeve of mine. A true zombie, like that featured in this film, is neither dead nor undead, though it does exist in a type of witchcraft-induced catatonia that resembles a living death. A ghoul, on the other hand, featured in everything from Night of the Living Dead to The Walking Dead, is a formerly living creature raised from the dead. Ghouls are undead. Ghouls feast on flesh. Zombies do not. ALL MODERN ZOMBIES ARE GHOULS. Thank you, that is all.

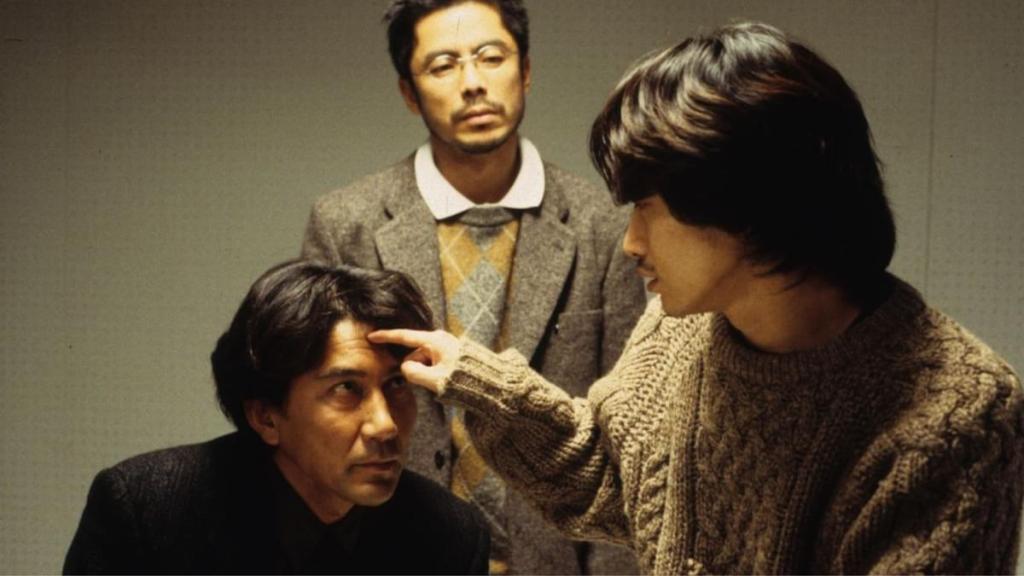

84. Audition (1999)

Aoyama Shigeharu (Ryo Ishibashi) and his teenage son Shigehiko (Tetsu Sawaki) are muddling through life after the death of wife and mother Ryoko (Miyuki Matsuda). It’s been seven years since her death, and Shigehiko is encouraging his father to find a new wife. When Shigeharu’s friend Yasuhisa (Jun Kunimura, The Wailing), a film producer, offers to stage a fake audition for a nonexistent television show in order to find him a wife, Shigeharu accepts. After a day of auditioning women with no reaction from Shigeharu, a young woman named Asami grabs his attention. Asami is twenty-four years old and embodies everything he’s looking for in a partner: a demure and intelligent nature with an interest in an artistic hobby, such as dance. Asami is quiet and polite, a ballet dancer with a traumatic background that Shigeharu immediately connects with. After a background check turns up some troubling information, Yasuhisa tries to convince Shigeharu that Asami is perhaps not who she seems, but he is determined to have her for his wife.

And down the rabbit hole we go.

In Audition nothing is as it seems. Shigeharu is patriarchal and controlling; Asami is an enigma; perhaps the only adult in the whole film whose point of view can be trusted is the slimy producer Yasuhisa. Throughout, Shigeharu never sees the real Asami, and this plays out over the course of the film in ways both literal and figurative. Is it because she is playing a part, or is it because Shigeharu refuses to see her as a real person instead of the ideal he’s built up in his head?

At turns a romantic comedy and a psychological thriller, with the extreme violence and surprising twists that Takashi Miike is known for, Audition keeps viewers on their toes. In the end, it’s all up for interpretation, and I won’t spoil anything by sharing any more of mine than I already have. Suffice it to say, this is a must watch if you can stomach its final act.

83. Häxan (1922)

Benjamin Christensen’s silent masterpiece is a faux-documentary, interspersed with gorgeously rendered dramatic reenactments over the course of seven chapters, tracking the evolution of beliefs in Satan and witchcraft, and how those beliefs were used to target people with mental disabilities and illnesses. From its pagan roots, through the Inquisition and witch trials, all the way to the present day, in this case meaning 1922, where “hysteria” is treated like possession, Haxan follows these stories of witchcraft ultimately attempting, in my opinion, to debunk them as so much misogynistic religious fanaticism.

Häxan is the earliest example of which I’m aware to use the documentary format to tell a horror story. With reenactments and interstitial artwork to help it along, it’s one of the most unique presentations of this early era of filmmaking, and one of the first to ask which is scarier: if the horror of our imaginings is real, or if we’ve simply created a way to destroy each other.

82. When Evil Lurks (2023)

Demián Rugna had been quietly releasing crime and horror films for a decade before his difficult to define but nonetheless stellar 2017 horror film Terrified (not to be confused with Terrifier) hit the scene with a jolt. With that busily plotted and thematically varied entry, he became a filmmaker to watch for me, so when When Evil Lurks dropped a few years later, I jumped on it, and was pleased to find an artist who had matured in every conceivable way. This is one of a couple of newer films that I’m already thinking will, given enough time, move even further up the rankings in future editions of this list.

When Evil Lurks is a film about sickness, an epidemic, but one in which it isn’t the immune system that’s attacked but a person’s very soul. When brothers Pedro (Ezequiel Rodriguez) and Jimi (Demián Salomón) find that one of their neighbors is harboring a “rotten”, or encarnado, a person infected with a demonic entity, after having found the cleaner who had been sent to their village to retrieve the infected man dead from apparent foul play in the nearby woods, they attempt to remove the rotten themselves, leading to a series of events that require the brothers to flee with their family in tow, across a country we now see has been teetering in a sort of slow-motion apocalypse for many years.

As an American viewer, it’s easy to give Rugna’s brutal masterpiece a thematic reading through the lens of our own government’s response to the Covid-19 pandemic, and if that’s how you connect to the work, I think that’s fine, as that interpretation is true to the spirit of Rugna’s intention, but during a Q&A at Fantastic Fest, the filmmaker said he had gotten the idea from news stories about the usage of dangerous pesticides in rural Argentina that had caused cancer and other health issues throughout the population, and the subsequent failure of the government to adequately respond to the crisis in the face of extreme corporate greed. This mundane evil lurks everywhere you look, but what happens when it’s allowed to spread unchecked? That is the question that Rugna’s film first asks, then answers, in a series of increasingly shocking events. From the first discovery of the bloated rotten to its Who Can Kill a Child-esque ending, the film revels in making the viewer watch as Pedro’s world collapses around him. When powers beyond his control are intent on evil, how could he, a simple family man, ever hope to combat them?

81. Misery (1990)

Paul Sheldon (James Caan) is a beloved romance author with fans around the globe. Too bad the universe didn’t see fit to send him any rescuer other than his number one fan, Annie Wilkes, after he runs his car off the road during a sudden snow storm. At first, this former nurse is a godsend, but when she learns that Paul has killed off her favorite character, Misery Chastaine, in his newest book, she holds him captive in a bedroom in her secluded home and forces him to write her a better ending. Will he be able to do the same for himself?

Kathy Bates won the Oscar for her portrayal of the iconic villain in Rob Reiner and William Goldman’s adaptation of the Stephen King novel of the same name, and it’s no wonder why. She plays the dual nature of Annie, at times saccharine sweet, at others vindictive and violent, to perfection. One waits with breath held for her next wild mood swing to see what danger or humiliation she has in store for Paul this time. It’s a claustrophobic film, largely set in the small bedroom where Paul is held, and Reiner does a great job of making the viewer feel like they’re trapped as well, ratcheting the tension up interaction by interaction. Touching on themes of toxic fandom and parasocial behavior, Misery feels like the kind of film that will perhaps always be relevant. It doesn’t hurt that it’s also one of the best thrillers ever made, comparable in all the best ways to classic Hitchcock.

80. Island of Lost Souls (1932)

After being shipwrecked in the South Seas, Edward Parker (Richard Arlen) is rescued by a freighter loaded with a shipment of live animals. After a fight with the freighter’s drunken captain over his treatment of a strange, animal-like crew member, Parker is unceremoniously tossed into a departing boat and taken to the island domain of Doctor Moreau (Charles Laughton), a fringe scientist who has set himself up as the local god to a race of human/animal hybrids, where he becomes dangerously embroiled in the doctor’s machinations.

Prior to helming a string of Universal monster sequels in the 1940s, workman director Erle C. Kenton was hired by Paramount to take on H.G. Wells’s “exercise in youthful blasphemy”, The Island of Doctor Moreau, after the success of the studio’s previous literary horror outing, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Skirting just under the wire of the implementation of the Hays Code, Kenton’s film is a disturbing trip through mad science, torture, “deviant” sexuality, and what it means for our humanity when we play god. If you’re looking for something a little darker than what Universal had on offer in the early 1930s, Island of Lost Souls is it.

79. Cure (1997)

Kyoshi Kurosawa’s (Pulse) crime thriller follows Detective Kenichi Takabe (Koji Yakusho) as he pursues a series of almost identical murder cases. In each case, the victim has an X carved into their neck, and their killer remains nearby, remorseful and awaiting arrest. These murderers all have something in common: each claims to remember their crime but has no recollection of their motive. As Detective Takabe slowly pieces together the facts with the help of psychologist Dr. Makoto Sakuma (Tsuyoshi Ujiki), it becomes clear that the murderers may in fact be victims themselves, bewitched in some way by a strange young man (Masato Hagiwara) who seems to wield a sinister power. Under the stress of his home life where he cares for his ailing wife and of the rigors of such an oblique case, Takabe’s investigation soon spirals into obsession, blurring the lines between reality and paranoia.

Kurosawa’s film is a stylistic, atmospheric dive into murder and madness, with no more than a passing resemblance to Se7en (1995), despite the earlier American film’s name often being bandied about in relation to Cure. Its horrors evoke a headier fear. Its answers are evasive. It’s the type of film that lives with you once you’ve seen it, sending you down the rabbit hole of Reddit threads and deep-dive blogs in search of answers that remain elusive but continue always to tease.

78. Martyrs (2008)

When Martyrs opens, we find Lucie (Mylene Jampanoi), armed with a shotgun, brutally dispatching an entire family. It seems she has finally tracked down the people responsible for the captivity and torture she endured as a child. This vengeance has been her life’s work, and it is now complete. When her friend Anna (Morjana Alaoui), also a victim of abuse, arrives to help Lucie clean up the scene, Lucie is attacked by an emaciated woman who may or may not be a product of her damaged psyche. To avoid spoilers, I will leave off right there. Suffice to say that from that point, we’re taken on a tour through trauma, madness, and a spiritual awakening that may or may not have been worth the price for those involved. The pacing is breakneck, the plot far-reaching, bringing to mind recent work of filmmakers like Zach Cregger (Barbarian, Weapons) and the Philippou Brothers (Talk to Me, Bring Her Back) as much as it does Pascal Laugier’s New French Extremity contemporaries—a definition he has admittedly attempted to distance himself from.

The problem I expect many viewers to find with Laugier’s brutal, bleak, and disturbing psychological horror film is that while its themes beg for repeat viewings, its content will likely mean you only have the stomach for one. But therein lies the film’s thesis. Its philosophical musings are dense and difficult, and it wants you to struggle to cut through to the meat of them; to learn finally that enlightenment requires violent transcendence. In Martyrs, form and function work in tandem.

77. Raw (2016)

Justine (Garance Marillier) is a vegetarian, a lover of animals, so it’s no surprise when she follows in her older sister Alexia’s (Ella Rumpf) footsteps and enrolls in the prestigious Saint-Exupery veterinarian school. The world she enters, however, is not at all what she expected, as she’s pushed into odd traditions and hazing rites. When one of these rituals requires Justine to eat meat for the first time in her life, it awakens in her a previously unknown animal nature.

Julia Ducournau’s (Titane) confident and stylized debut feature is a Cronenbergian feat of genre filmmaking that turns the classic bildungsroman into a body horror nightmare of passion and absurdity, a sexually charged film that functions as both tragedy and comedy. Watching Justine navigate this world that upon first glance looks so much like our own before ultimately devolving definitively into bizarro realism requires an unflinching constitution, a resolve to follow wherever Ducournau and her talented young actors wish to take us, even when that place is a climax that owes as much to the “finger-bang misfire” scene in Cabin Fever (2002) as it does the art house.

76. Candyman (1992)

In the late 1800s, Daniel Robitaille, artist, lover, son of slaves, is commissioned by a former plantation owner to paint a portrait of his daughter, Caroline. After Daniel and Caroline fall in love, resulting in Caroline’s pregnancy, Daniel is run out of town, pursued from Louisiana to Chicago by the hired men of the plantation owner, where he is subsequently tortured, lynched, and then burned. A hundred years later, the ghost of Daniel Robitaille is said to haunt the site of his murder, the Cabrini Green public housing complex, by those who call the high-rise tenements home, killing anyone who says “Candyman” five times while looking into a mirror.

Grad student Helen Lyle (Virginia Madsen) runs afoul of the titular hook-handed specter while researching urban legends and folk tales for her doctoral thesis with her research partner and best friend Bernadette Walsh (Kasi Lemmons). Diving headlong down the rabbit-hole of racial and economic inequality and the evils visited upon African Americans in the years after the Civil War, during and after Reconstruction, and how that evil still plays out today (both in the year the film was released and unfortunately still upon this writing, which is why the sequel/reboot from 2021 works so well, and you should see it if you haven’t) Helen becomes obsessed by the story of the Candyman, alienating her husband and her friends with her increasing belief in the actual, really for real, not just a boogeyman meant to explain away the poverty and violence in which the people of Cabrini Green live, real life Candyman. When her belief leads her to say his name in a mirror, she finds her obsession reflected back at her.

Candyman is a thematically rich slasher that works equally well as horror and social commentary, something that I don’t think the viewers or critics of the time were ready for, judging by the contemporaneous critical consensus. In my view, Bernard Rose’s take on the Clive Barker short story reads as more insightful now than it probably did for many viewers upon release who may have been looking for a simple supernatural slasher (not that there’s anything wrong with that) more along the lines of A Nightmare On Elm Street (1984). It’s also atmospheric as hell, with haunting music by the minimalist composer Phillip Glass and production design by Jane Ann Stewart that brings to life the crumbling and graffitied structure of Cabrini Green, rendering it a character in its own right. It’s also one of the most expertly acted horror films of its era.

Candyman hints at an unrealized world in which the intelligent, adult horror of the 60s and 70s might have continued to be expertly combined with the delightful schlock of the 80s slasher. Alas, it wasn’t meant to be, and the film stands as the lone example.

75. The Devil’s Backbone (2001)

After the death of his father during the Spanish Civil War, 12-year-old Carlos (Fernando Tielve) is sent to live at a remote orphanage run by Republican loyalists Casares and Carmen in the Spanish countryside. Because of their political activities, including the keeping of a large cache of gold used to support the Republican treasury, the orphanage has been subject to attacks from the fascist Nationalists. At the center of the courtyard lies a massive inert bomb leftover from one such attack. The night the bomb was dropped is surrounded in mystery, and a burgeoning legend about a boy named Santi who went missing that same night is whispered of by the boys of the orphanage. When Carlos encounters a ghostly apparition, a boy with a bleeding wound on his head, one night after hearing strange noises, he gets the other boys together to investigate the many mysteries that seem to flourish inside this boys’ school.

While Pan’s Labyrinth is more indicative of the lush visual style Guillermo del Toro is known for, it’s his earlier take on the same theme of a lonely child suffering the effects of the Spanish Civil War that best exemplifies the huge heart at the center of much of his work. Though in many ways, The Devil’s Backbone is a smaller film than any that del Toro has produced in the years since its release, set as it is entirely inside the walls of the haunted orphanage, it is massive in its thematic scope and lavishly melodramatic in its depiction of the dark secrets that simultaneously hold the walls of this fortified home aloft and threaten to send them crashing down. For me, this is the stronger of the two thematically similar films that make up two thirds of the loosely assembled trilogy that also includes his incredible 1993 vampire film Cronos. Del Toro presents a fresh take on gothic horror that puts The Devil’s Backbone in league with other turn-of-the-millennium classics like Amenábar’s The Others.

74. The Invitation (2015)

Karyn Kusama’s (Jennifer’s Body) tension-filled psychological horror masterpiece about a man who accepts an invitation to a dinner party hosted by his ex-wife and her new partner is an exercise in extreme discomfort, a spiraling look into the individual ways in which we deal (or refuse to deal) with tragedy. Featuring an incredible cast, including a realistic and relatable turn from Logan Marshall-Green and John Carrol Lynch at his sinister-by-way-of-affable best, and a tightly structured script by Phil Hay and Matt Manfredi, Kusama’s low budget, bottle-episode-esque film is one of the best of the decade.

I have a lot to say about The Invitation, but if you still have the luxury of going in blind to a decade old film, I wish for you to remain able to do so, so I’m keeping this one short and sweet.

73. Scream (1996)

In Scream, high-schooler Sidney Prescott (Neve Campbell) is targeted by a masked killer one year after the violent assault and murder of her mother Maureen in the fictional town of Woodsboro, California. Under the impudent scrutiny of investigative journalist Gail Weathers (Courteney Cox), who believes in the innocence of Cotton Weary (Liev Schreiber), the man convicted of killing Maureen—going so far as to write a book about it—and the bumbling but well-meaning protection of sheriff’s deputy Dewey Riley (David Arquette), Sidney fights back against the killer dispatching her friends one by one and a media that’s more interested in turning her into a story than uncovering the truth.

Wes Craven introduced meta-horror to the masses with his 1994 riff on his own A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984), New Nightmare, but it was this collaboration with screenwriter Kevin Williamson that began to tackle, with laser focus, the rules underlying the slasher, horror’s supposed effects on the real world, and the media’s commodification of sensational crimes. The strength of the Scream franchise as a whole, and of this first film specifically, is that it’s interested in more than satirizing and subverting the genre, though it does both exceedingly well; it uses its fun-poking to prod at deeper societal issues, such as the media’s role in sensationalizing female trauma, the public’s insatiable appetite for violence, and the dangers of angry young men when they’re deprived of what they believe they’re owed. Whether it was Williamson’s intention is up for debate, but it’s difficult today to read this film as anything less than a treatise on violent misogyny, both on a personal level and from our media elite. It’s also a hell of a fun ride. The film’s dual nature holds a mirror up to the viewer, implicating us as well. Once again, form and function working in tandem is a sure way to get your movie on my list of favorites.

Fun fact: Scream’s original title during the time that Williamson was shopping his script around was Scary Movie.

72. 28 Days Later (2002)

Bike courier Jim (Cillian Murphy) awakens from a 28-day coma to find a world ravaged by a “rage” virus that has turned the population into fast-moving monsters set on violently infecting any survivors who yet remain. The film is heavily inspired by John Windham’s 1951 novel The Day of the Triffids, in which England is taken over by alien plant-life. In this novel, a ragtag group of survivors flee across the country in search of help, encountering along the way the nefarious remnants of a former military unit who promise help but have other motives. 28 Days Later follows this same basic structure, with Jim and a string of fellow survivors, played by Naomie Harris and Brendan Gleeson, among others, joining him on his cross-country trek. After days of traveling in search of safety, the group believes they’ve found it in Major Henry West (Doctor Who’s Christopher Eccleston) but the Major has troubling plans for the female survivors.

Shot entirely on digital, Danny Boyle and Alex Garland’s 28 Days Later was meant to evoke a vision of reality, of the immediacy inherent in its fast format that mirrors the threat posed by those infected by the rage virus. Instead, watching today, it shows us a transitional moment in film history in which technology had not yet caught up to intent. The film is dark and grainy, pixelated at times, showing us a vision of the past instead of the always-present, but it’s exactly this that allows it to function as an important relic of its time, a glimpse into the psyche of a nation and culture seemingly on the brink of self-destruction. Garland’s nihilistic view of his fellow Englishmen helped shape the aesthetics of the zombie revival of the aughts that can still be felt today, though it should be noted that neither Danny Boyle nor myself—I’ve already established my rigid definition of what constitutes a zombie in this very list—considers this to be a zombie film.

71. Green Room (2015)

Pat (Anton Yelchin), Sam (Alia Shawkat), Reese (Joe Cole), and Tiger (Callum Turner), members of the Ain’t Rights, a punk band from Washington, DC, are traveling in their van through the Pacific Northwest on a tour that has brought them to Portland, Oregon. They’re low on funds and gas, and are currently living show to show. When they learn that their next gig has been canceled, throwing their plans into disarray, local music journalist Tad (David W. Thompson) tells them of a bar out in the sticks that can fit them into their lineup. He informs them that it’s a skinhead bar, but it pays $300, and since they have to get paid if they’re to continue their tour, they agree to sell out just this once.

During The Ain’t Rights’ set, opening for National Socialist Black Metal band, Cowcatcher, Pat sees two young women, Emily (Taylor Tunes) and Amber (Imogen Poots), looking uneasy and being roughly escorted out of sight. After the performance, Pat, Sam, Reese, and Tiger attempt to make a quick exit, feeling regrets about the whole scene and sensing a threat in the air, but Sam realizes she’s left her phone in the green room. Pat volunteers to retrieve it and heads for the green room where he stumbles upon the members of Cowcatcher standing over Emily’s corpse. Pat runs, calling the cops as he goes, but he’s hauled back into the green room along with his band mates. Realizing quickly how out of control the situation might become, they lock themselves in the room, taking one of the nazis hostage. This obviously doesn’t help smooth things over.

What follows over the next hour of the film’s runtime are some of the most intense sequences of cat-and-mouse violence ever put to film. Writer-director Jeremy Saulnier (Blue Ruin) elevates what could otherwise be a simple exploitation flick into the realm of horror/thriller classics, a claustrophobic slasher that gets turned on its head so many times as the tide of war shifts between The Ain’t Rights and Darcy’s (Patrick Stewart, in a rare sinister turn) crew of skinheads, that all sense of who is predator and who is prey gets lost. Though it’s refreshingly never difficult to tell who the bad guys are.

For anyone confused about what happens if you give even a single inch of space for nazis, the wrist-vs-cracked-door scene is for you.

70. The Vanishing (1988)

Three years after Rex’s girlfriend Saskia disappeared from a busy roadside service station while the Dutch couple were on a cycling vacation in France, we find Rex (Gene Bervoets) obsessed with learning the truth of what happened that day, his life dark and diminished by Saskia’s mysterious disappearance. When Rex begins to receive postcards from a man named Raymond (Bernard-Pierre Donnadieu) claiming to have been Saskia’s (Johanna ter Steege) kidnapper and offering to show him the truth of what happened that fateful day, he must choose between enacting justice and slaking his curiosity.

Drawing on influences ranging from Hitchcock to Clouzot, George Sluizer’s thriller—not to be confused with his own lesser 1993 American remake—drips with tension. It’s a pitch-black look at what makes these two men tick. For Raymond, the perpetrator, a life of cliched banalities leads him to seek thrills in the forbidden; for Rex, the victim (or so he sees himself), one unexplained violent act has defined his life. Together, the two men journey down the dark path of self-absorption in search of a meaning that lies forever out of reach. The journey is bleak; the destination is bleak; one imagines Sluizer believes life itself is bleak. There are no jump-scares here, no cheap thrills, not even that much blood to speak of, but The Vanishing is one of the most horrifying films on this list.

69. Speak No Evil (2022)

In Christian and Mads Tafdrup’s film, Danes Bjørn (Morten Burian) and Louise (Sidsel Siem Koch), along with their young daughter Agnes (Liva Forsberg), are on holiday in Tuscany where they meet kind, gregarious Dutch couple Patrick (Fedja van Huêt) and Karin (Karina Smulders) and their son Abel (Marius Damslev) who suffers from a condition that renders him unable to speak. The two couples, sans children, dine together that evening; Their conversation is wide-ranging—from the similarities in Dutch and Danish cultures, to Patrick’s disdain for boring, politically correct people, to Louise’s vegetarianism—and they all have a wonderful time, especially Bjørn who, feeling a little unsure in his own skin, seems drawn to Patrick’s masculine confidence and willingness to say things others might be afraid to.

Months after their holiday has concluded, Bjørn and Louise receive a letter in the mail from Patrick and Karin inviting them and Agnes to come visit at their home in the Dutch countryside. Louise is reticent, but once Bjørn learns that it’s only an eight hour drive, and another of their friends so helpfully points out “what’s the worst that could happen?”, Louise concedes.

The rest of the film plays out at Patrick and Karin’s deteriorating split-level house, where minor inconveniences pile up—the house is a mess, the couple seems—either blissfully or maliciously—to completely disregard Louise’s dietary restrictions, and Agnes, unable to feel safe or comfortable on the floor in Abel’s room where Patrick and Karin have insisted she sleep, nightly climbs into the twin bed in the small room where Bjørn and Louise are staying.

Patrick and Karin push boundary after boundary, and on the rare occasions that Bjorn or Louise express discomfort at their hosts’ behavior, the couple is full of logical-sounding excuses and earnest apologies. Bjørn and Louise decide to finish out the weekend, feeling chastened by the couple’s calm reasonableness and embarrassed to have made such a scene. In Carlos Aguilar’s 3 1/2 star review for Rogerebert.com, he uses the phrase “plausible deniability of malice” which I think succinctly sums up what’s so sinister in the gaslighting that Patrick uses throughout the film and what feels so personally recognizable and terrifying: the remembrance of all the times you’ve been made to question your own judgment and have relied on the expected goodness of others.

In the film’s bleak, devastating climax, which I won’t spoil here, Bjørn asks of Patrick, “Why are you doing this?” and Patrick replies, “Because you let me.” It’s this small moment of heavy-handedness in an otherwise smartly nuanced script that hammers home the point of the Tafdrup brothers’ cautionary tale: that the road to hell is paved with social niceties. It also works as a moment of release meant to let the viewer off the hook, because obviously you wouldn’t let someone do this, right? It’s invites you to pick apart the behaviors of its protagonists, and to pinpoint the spot at which you, personally, would say, “this far and no further,” and once you’ve watched Bjørn and Louise allow your own personal line to be crossed, to blame them for whatever happens to them next. It’s a film that, I believe, wants to make you the bad guy.

Perfectly acted and beautifully shot, with a nuanced script that will have you thinking of several exchanges well after the movie ends, Speak No Evil is a brilliant display of realist filmmaking. There are no flourishes here, and it’s groundedness allows for the language of the filmmaking to get out of its own way, and to lay out its quickening beats one after another until they’ve backed you into a corner you can’t escape from. You can only stand by, watching.

Of course you could simply say “Move! Let me out!”

But would a nice person do that?

Of course not.

68. The Brood (1979)

At the Somafree Institute of Psycho-Plasmics, Dr. Hal Raglan (Oliver Reed) treats his troubled patients with a controversial therapy of his own devising, wherein their psychological symptoms are made physical so that they may be excised like cancer. Among these patients is Frank Carveth’s ex-wife Nola (Samantha Eggar). Recently, Dr. Raglan has begun seeing both Nola and their daughter, Candice, against Frank’s wishes. When Candace comes home from one such treatment, Frank (Art Hindle) discovers bruises all over her body. After a confrontation with the famous doctor, Frank begins to learn the truth, not only of his wife’s treatment and his daughter’s injuries, but of the mysterious deaths that have been occurring all over town.

The Brood is Cronenberg’s most personal film. Conceptualized during the aftermath of his own messy divorce, this paean to marital hatred, with its monstrous custody battle, is the body horror answer to Kramer vs. Kramer, and I, like Cronenberg himself has asserted, find it to be the more truthful of the two films.

67. Poltergeist (1982)

I saw Poltergeist for the first time sometime around 1990, which would have put me around 8 years old, while peaking around the doorframe of my darkened bedroom down the short hallway toward the living room television, a 25” black plastic and faux-wood Zenith, as my parents watched it on HBO. I couldn’t see much from that distance, but quickly found that one did not need to make out every detail of the clown doll, the gnarled limbs of the tree outside the window clawing, reaching, grabbing, or Carol Anne conversing with the snowy television to know that this was the real deal. It was a formative experience in my horror education. I consider that night, along with watching Frankenstein (1931) earlier that same year and both watching and reading Pet Sematary the next, to be the official beginning of my lifelong obsession.

Watching Poltergeist with the eyes of an adult, it’s easy to dismiss it as a horror movie for children, and while there is admittedly a cartoon-like quality to some of its frights, it’s everything you don’t notice as a child that sets it apart from other haunted house fare, something that many haunted horror films of the 2010s resurgence tried, and failed, to capture: a real family made up of real people trying their best to hang onto each other as the world they’ve clawed out for themselves is upended by forces outside of their control. There is a genuineness here bolstered by the central relationship between parents Steve (Craig T. Nelson) and Dianne (JoBeth Williams) and their children. Poltergeist, directed by Tobe Hooper and written by Steven Spielberg, is a story of borderlands; between life and death, sure, but also between parenthood and personhood—we see Steve and Dianne genuinely enjoying each other’s company, being individual people with individual dreams, while sharing a late-night joint, as well as being kind and present parents to their children—and between the middle-class and poverty, Steve having worked hard to be able to afford this brand-new home when a deal from his company presented itself while never losing the fear of destitution were they to pack up and run in the face of this demonic presence that has taken over their lives. It feels like a snapshot of its time, a time in which if you worked hard and dealt honestly, you could build a life for your family, but, in keeping with borderlands, a time when greed had already begun to bleed in and corrupt. Spielberg’s script is strong, and whatever the film has lost in scares, it makes up for in being always relevant.

66. Train to Busan (2015)

While on a train headed from Seoul to Busan, a work-obsessed father’s already tense travels with his young daughter Soo-ann (Kim Su-an) are transformed into a frenzied fight for survival when a virulent outbreak spreads like wildfire among passengers and crew alike. With the help of his daughter and a cast of colorful fellow passengers including working-class-hero, Sang-hwa (Ma Dong-seok), Seok-woo will learn that the only way to survive is to work together.

Yeon Sang-ho’s action-packed horror-thriller is the best straight-up “zombie” movie of the 21st century, a variation on Garland and Boyle’s fast, rage-filled take on zombies but with much more heart and humor. To be sure, tragedy and gore abounds on this cross-country nightmare, but you’ll be cheering right up until the train pulls into the station.

65. The Endless (2017)

After receiving a mysterious video tape from the death cult they escaped from as young boys, brothers Justin (Justin Benson) and Aaron (Aaron Moorhead) are at loggerheads about what to do next. Their lives have been difficult since leaving the cult, with older brother Justin having done his struggling best in caring for himself and Aaron, and Aaron quietly resenting his brother for taking him away from his bountiful childhood with the cult and depositing him into a life of soulless toil and meaningless survival. Aaron doesn’t understand why they had to leave, and Justin has never managed to convince him that they were in actual danger, so when Aaron sees his chance to return to the place he still thinks of as his home, Justin reluctantly agrees to accompany him in the hope that, with the eyes of adulthood, his little brother will finally see the cult for the very real threat it poses. When the brothers arrive at the desert compound, they find things shockingly unchanged, including the members themselves seemingly having escaped the effects of aging. The Endless is endlessly spoilable, so I will stop there in my description. Suffice it to say, that things get stranger the longer the brothers spend with their former family, and even Justin eventually finds himself doubting his own judgment after a bizarre ritual involving a game of tug-of-war with an invisible being in the sky.

Yeah.

Best enjoyed as a double-feature with their debut film, Resolution (2012), though more than strong enough to stand on its own merits, DIY writing and directing duo Justin Benson and Aaron Moorhead’s indie opus is not only their best film to date, but one of the most original cosmic horror films of all time.

64. Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer (1986)

Bringing the realism of New Hollywood to the slasher genre, John McNaughton’s controversial film follows Henry, Michael Rooker in his debut role, as he embarks on a spree of random murder across a gritty, grimy 1980s Chicago. Henry is fresh into town and staying with his old cellmate, Otis (Tom Towles) when he finds his living situation suddenly disrupted by the arrival of Otis’s sister, Becky (Tracy Arnold). Becky’s presence cuts a rift between Henry and Otis’s tenuous friendship as Otis begins to show a violently incestuous interest in his own sister. In an attempt to draw him away from Becky, Henry drafts Otis into his life of senseless murder, and after a brief reluctance, Otis takes to it with a zeal that discomfits even Henry. Bodies begin to fall with unsustainable frequency. Through Henry’s interactions with his housemates, we begin to see a complex, nuanced side to his character, a man who has a code of ethics that doesn’t so much make the viewer sympathize with him as it makes his psychopathic actions even less sensible. It’s a tightrope walk that filmmakers and storytellers before and since have mostly failed to execute. Films like Psycho and Peeping Tom have successfully shown us sympathetic killers, but not until Henry are we given one who is presented in all his flawed humanity and yet whose reasoning for his actions remains opaque.

Henry has spent the past several years in prison for the shooting death of his mother, a fact we are privy to early in the story, the truth of which we assume will be elucidated as the story unfolds. As a savvy viewer, we expect the details of this to shed some sort of light on Henry’s behavior as an adult, but later, when Becky asks Henry about his mother, he claims to have stabbed her to death. In any other film, this would serve as the villain’s origin story, the reason they do what they do, but for Henry, he’s told this story many times before, and each time his story is different; he has bludgeoned her with a baseball bat; he has shot her to death. His treatment of what would otherwise be our entry point to understanding shows us that even this monumental occurrence in his life can be reduced to thin lies, not so much obfuscations for his personal protection as they are light bits of fun for Henry. There is, in the end, no grand reveal. We know Henry, but knowing doesn’t equal understanding. He murdered his mother, as he has so many since, simply because he is a murderer. It’s oddly refreshing.